What is bladder cancer?

Bladder cancer is a common cancer and ranked ninth place in global cancer incidence in 2022, with more than 400 new cases reported annually in Hong Kong1,2. The most common symptom is haematuria (blood in urine), which appears in more than 80% of bladder cancer patients3. Although the prognosis is good when bladder cancer is diagnosed at early stages4,5, bladder cancer often recurs5-7, which means bladder cancer survivors will need to receive long-term surveillance and monitoring for any recurrance5.

Symptom

As bladder tumours are fragile and tend to bleed, haematuria is the most common symptom of bladder cancer. Haematuria can be either gross (you can see blood with the naked eye) or microscopic (red blood cells can only be seen under a microscope). However, apart from tumour, haematuria can be caused by other benign conditions, such as urinary tract infection, prostatic hyperplasia and mensuration8. Therefore, the specificity of haematuria for bladder cancer detection is relatively low8.

Screening method

Visual examination of the bladder by cystoscopy is the gold standard of bladder cancer diagnosis9. There are two main types of cystoscopies: flexible and rigid, with flexible cystoscopy commonly used10. Flexible cystoscopy is a procedure performed with a cystoscope, a long flexible camera approximately 5mm in diameter. The cystoscope is passed through the urethra and into the bladder. The doctor can observe the inside of the bladder from the images captured by the cystoscope and take cells or tissues from the bladder lining for further examinations11,12. However, cystoscopy is an invasive procedure and may cause complications such as bleeding, urinary tract infection and bladder perforation13. Moreover, fewer than 30% of patients are diagnosed with bladder cancer after cystoscopy14,15, indicating that a large portion of the affected individuals received invasive, expensive and uncomfortable procedures.

Therefore, there is a need for a non-invasive and user-friendly screening method to detect bladder cancer accurately in all stages at a reasonable price. Moreover, there is also a need to provide bladder cancer survivors with a reliable and convenient follow-up measure.

Introducing GALEASTM Bladder

GALEASTM Bladder was developed by British biotechnology company Nonacus Ltd. in collaboration with an expert team in urothelial cancer research at the University of Birmingham, UK, led by Professor Richard T. Bryan. It is an innovative genetic test for bladder cancer that analyses genomic DNA in urine samples through next-generation sequencing (NGS) to detect key genetic mutations present across all malignant grades and stages of bladder cancer with high sensitivity and accuracy.

Why choose GALEASTM Bladder?

Non-ivasive

| Uses a simple urine sample |

Minimizing the use of unnecessary invasive procedures

| Can be used as a triage before cystoscopy |

Highly sensitive detection

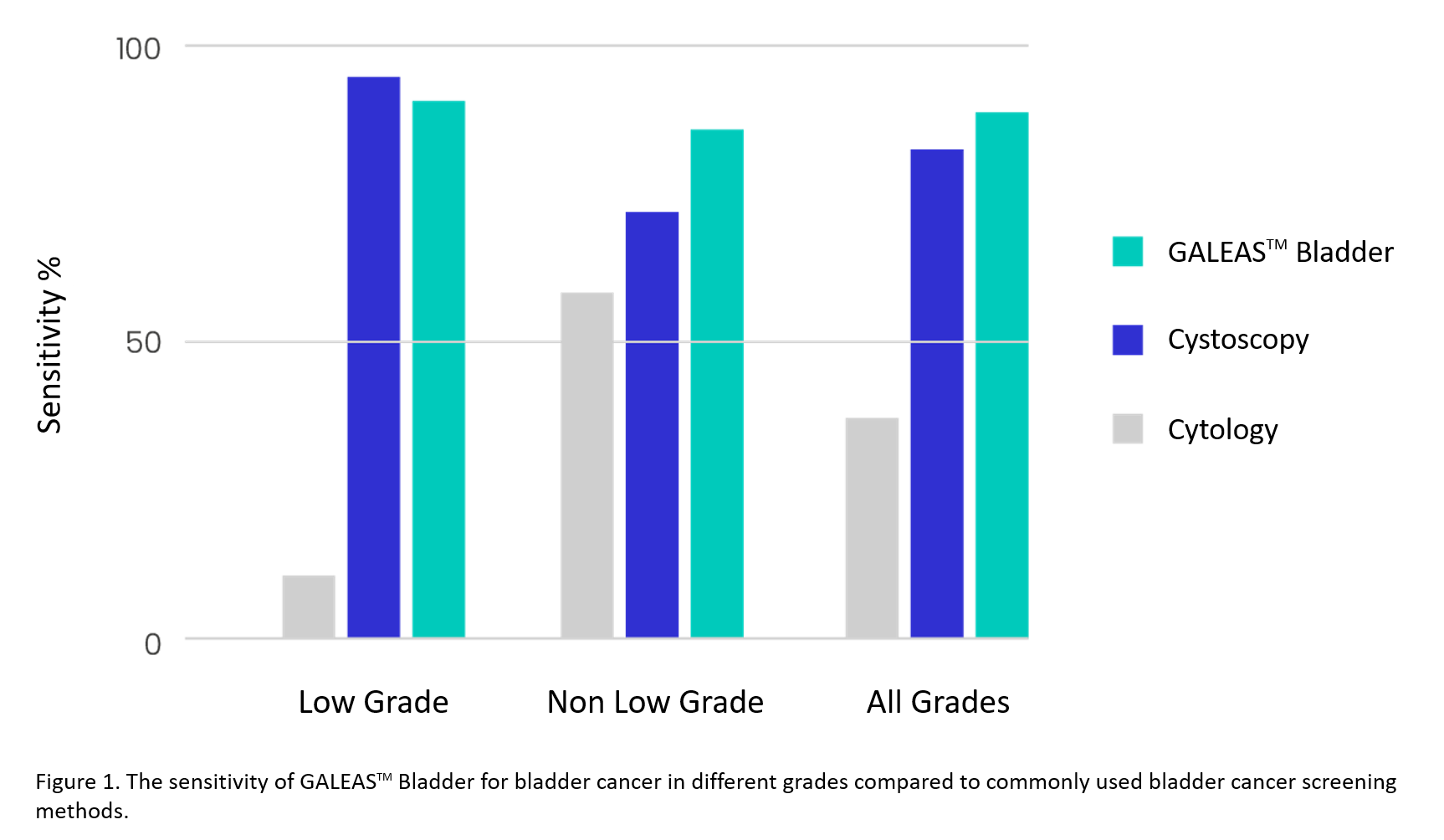

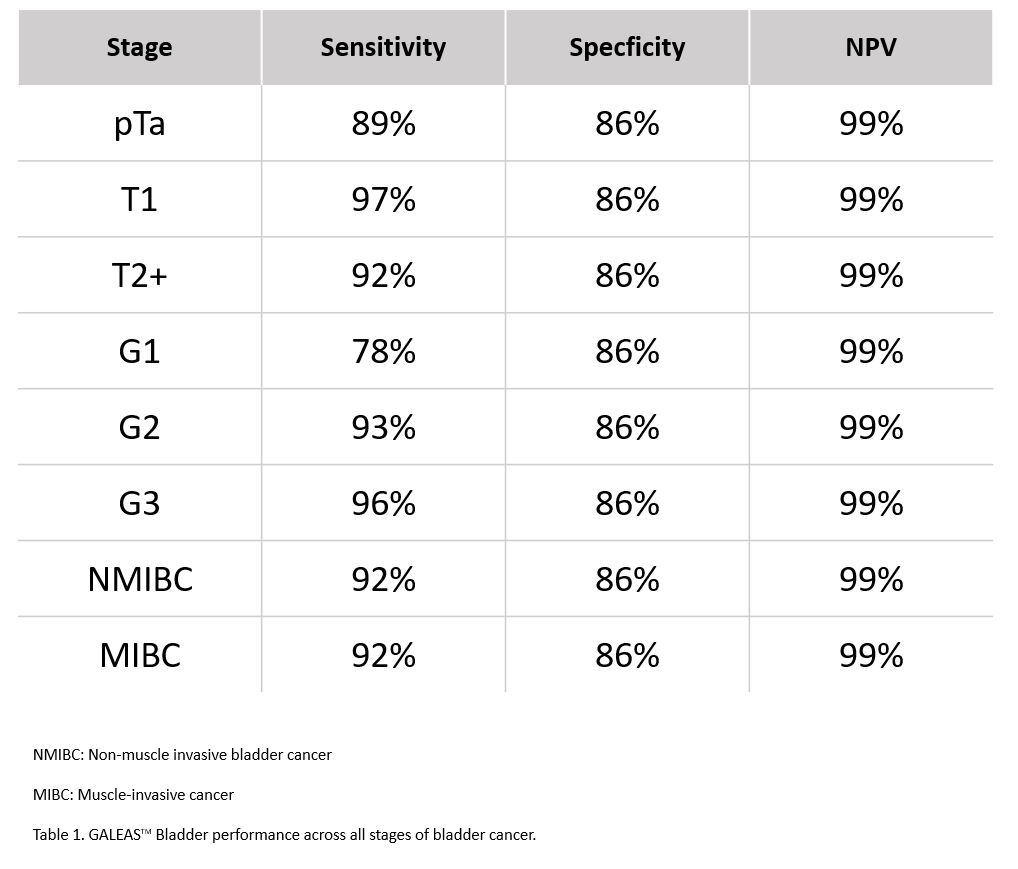

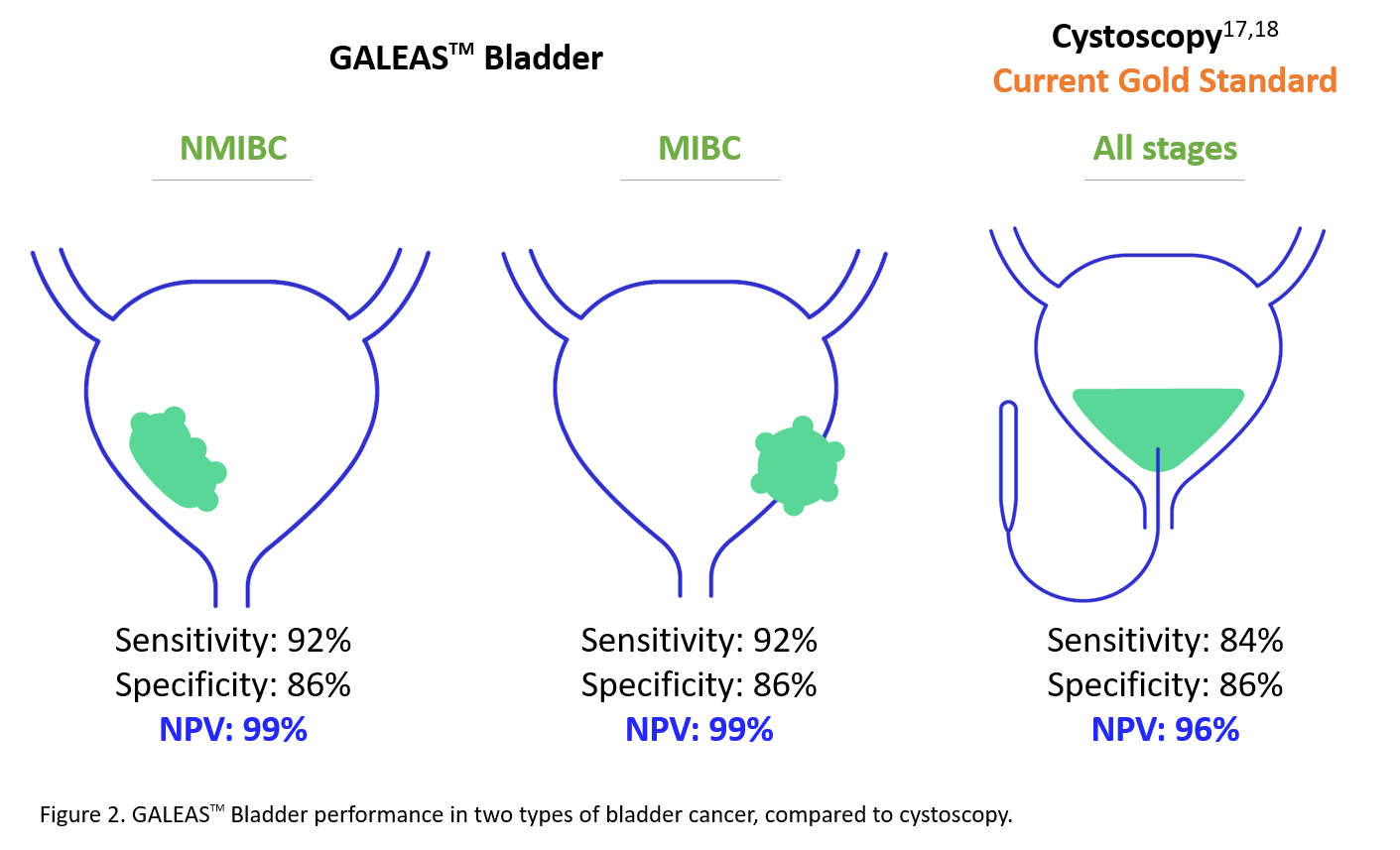

| Uses ultra-sensitive NGS technology to detect somatic mutations present in more than 96% of bladder cancer cases16 with a comparable performance to cystoscopy |

Validated in clinical studies

| Has been validated using 710 urine samples from 3 UK clinical studies16, ensuring high accuracy and reliability |

Test specifications

| Test code | Methodology | Sample requirement | Turnaround time |

|---|---|---|---|

| ONB | NGS | 50ml urine (First morning urine is NOT required; Sample should be stored at room temperature) | 3-4 weeks |

References

- 1 “Worldwide Cancer Data | World Cancer Research Fund.” World Cancer Research Fund, 19 Dec. 2024, www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/cancer-statistics/worldwide-cancer-data.

- 2 “Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority.” Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority, 12 Nov. 2024, www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/allages.asp.

- 3 “Symptoms of Bladder Cancer.” Cancer Research UK, 15 Sept. 2022, www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/symptoms.

- 4 “Bladder Cancer Prognosis and Survival Rates.” Cancer.gov, 27 Apr. 2023, www.cancer.gov/types/bladder/survival.

- 5 Goodison, Steve, et al. “Bladder Cancer Detection and Monitoring: Assessment of Urine- and Blood-Based Marker Tests.” Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy, vol. 17, no. 2, Mar. 2013, pp. 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40291-013-0023-x.

- 6 Loras, A., et al. “Bladder Cancer Recurrence Surveillance by Urine Metabolomics Analysis.” Scientific Reports, vol. 8, no. 1, June 2018, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27538-3.

- 7 Chamie, Karim, et al. “Recurrence of High‐risk Bladder Cancer: A Population‐based Analysis.” Cancer, vol. 119, no. 17, June 2013, pp. 3219–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28147.

- 8 Shirodkar, Samir P., and Vinata B. Lokeshwar. “Bladder Tumor Markers: From Hematuria to Molecular Diagnostics – Where Do We Stand?” Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, vol. 8, no. 7, June 2008, pp. 1111–23. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737140.8.7.1111.

- 9 Ye, Zhangqun, et al. “A Comparison of NBI and WLI Cystoscopy in Detecting Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Prospective, Randomized and Multi-center Study.” Scientific Reports, vol. 5, no. 1, June 2015, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10905.

- 10 SH HO Urology Centre, CUHK. www.surgery.cuhk.edu.hk/shho-urology-centre/health-cystoscopy.asp.

- 11 Lenis, Andrew T., et al. “Bladder Cancer.” JAMA, vol. 324, no. 19, Nov. 2020, p. 1980. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.17598.

- 12 “What Is a Cystoscopy.” nhs.uk, 14 Feb. 2024, www.nhs.uk/conditions/cystoscopy/what-is-a-cystoscopy.

- 13 Devlies, Wout, et al. “The Diagnostic Accuracy of Cystoscopy for Detecting Bladder Cancer in Adults Presenting With Haematuria: A Systematic Review From the European Association of Urology Guidelines Office.” European Urology Focus, vol. 10, no. 1, Aug. 2023, pp. 115–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2023.08.002.

- 14 Buntinx, F., and H. Wauters. “The Diagnostic Value of Macroscopic Haematuria in Diagnosing Urological Cancers: A Meta-analysis.” Family Practice, vol. 14, no. 1, Feb. 1997, pp. 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/14.1.63.

- 15 Sutton, James M. “Evaluation of Hematuria in Adults.” JAMA, vol. 263, no. 18, May 1990, p. 2475. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1990.03440180081037.

- 16 Ward, Douglas G., et al. “Highly Sensitive and Specific Detection of Bladder Cancer via Targeted Ultra-deep Sequencing of Urinary DNA.” European Urology Oncology, vol. 6, no. 1, Apr. 2022, pp. 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euo.2022.03.005.

- 17 Zhu, Chao-Zhe, et al. “A Review on the Accuracy of Bladder Cancer Detection Methods.” Journal of Cancer, vol. 10, no. 17, Jan. 2019, pp. 4038–44. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.28989.

- 18 Alimi, Quentin, et al. “Reliability of Urinary Cytology and Cystoscopy for the Screening and Diagnosis of Bladder Cancer in Patients With Neurogenic Bladder: A Systematic Review.” Neurourology and Urodynamics, vol. 37, no. 3, Sept. 2017, pp. 916–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23395.